Collection: Earthenware-Charai Taba Andro Pottery, Meghalaya Black Pottery, Thongjao Pottery

-

Kadhai de cuisine fossile

Prix habituel Rs. 3,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Marmite fossile

Prix habituel Rs. 3,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Casserole en grès de poterie noire Longpi | 2 litres

Prix habituel Rs. 5,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Cocotte en grès de poterie noire Longpi avec ailes à rabat 2 litres

Prix habituel Rs. 5,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

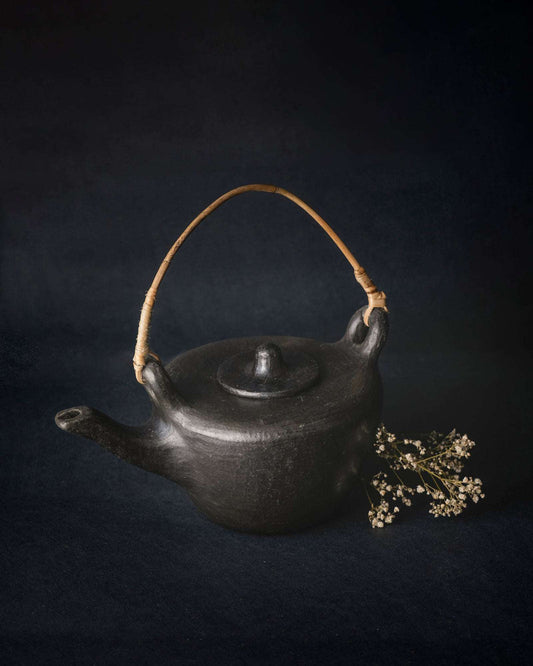

Bouilloire Novel en grès noir Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 2,800.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Bouilloire en grès de poterie noire Longpi - 1 L

Prix habituel Rs. 2,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Longpi Courage gagne toutes les guerres, nous dit ce petit rouge-gorge

Prix habituel Rs. 1,250.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Longpi Poterie Noire Grès Grande Marmite-3L

Prix habituel Rs. 5,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Longpi Poterie noire Grès Cuisson Handi

Prix habituel Rs. 3,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

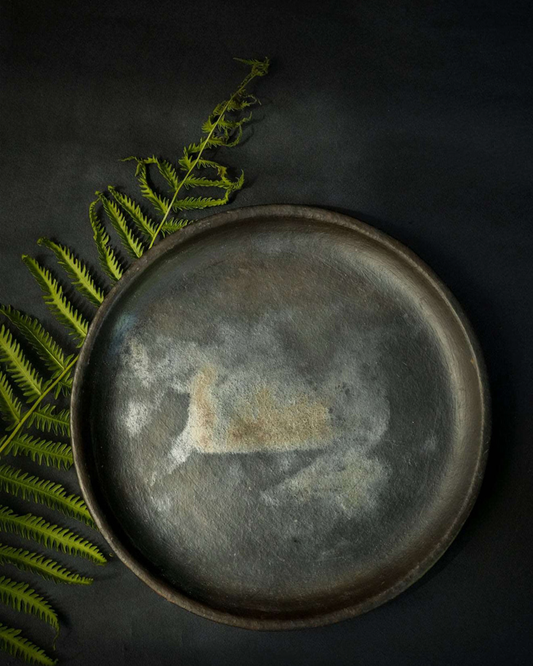

Assiette ronde en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 1,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Plateau ovale en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 2,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Assiette de boulanger en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 2,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Bol en grès moderne en poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 1,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Longpi Poterie Noire Grès Rond Kadhai

Prix habituel Rs. 3,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Épuisé

ÉpuiséLongpi Ô Coucou !

Prix habituel Rs. 1,250.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Épuisé

ÉpuiséLe vol du coucou Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 1,250.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Service à thé en grès de poterie noire Longpi avec bouilloire

Prix habituel Rs. 8,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

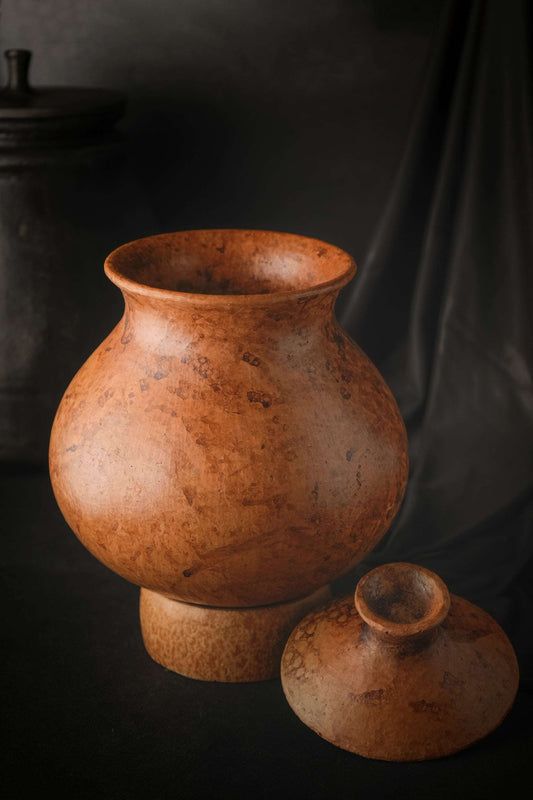

Petit pot de rangement en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 1,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Pot de rangement moyen en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 2,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Théière et serveur Longpi Black Pottery

Prix habituel Rs. 6,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Bouilloire en grès de poterie noire Longpi - 1 L

Prix habituel Rs. 2,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Casserole ou marmite en grès de poterie noire Longpi

Prix habituel Rs. 3,500.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Tasse à thé en poterie noire avec couvercle

Prix habituel Rs. 999.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par -

Andro Yu Grande Marmite 6L

Prix habituel Rs. 6,000.00 INRPrix habituelPrix unitaire / par

Abonnez-vous à nos emails

Abonnez-vous à notre liste de diffusion pour recevoir des informations privilégiées, des lancements de produits et bien plus encore.